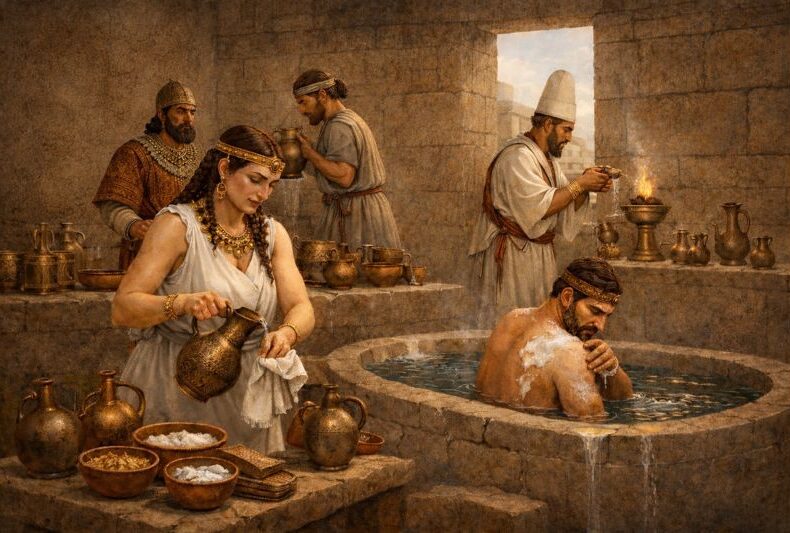

Scientific Study Reveals: The Hittites Practiced an Advanced Hygiene Culture 3,000 Years Ago

Long before modern concepts of sanitation emerged, the Hittites appear to have developed a surprisingly structured and disciplined approach to cleanliness. A new scientific study demonstrates that hygiene in Hittite society was not a marginal habit, but a core element shaping daily life, religious practice, and social order in Late Bronze Age Anatolia.

The research, published in Anatolian Studies and conducted by Ana Arroyo of the Complutense University of Madrid, brings together cuneiform texts and archaeological evidence to reassess how cleanliness was understood and practiced in the Hittite world. Its conclusions challenge the persistent assumption that ancient hygiene was primitive or purely symbolic.

Cleanliness as Order, Not Convenience

According to the study, the Hittites did not treat hygiene as a single, uniform concept. Cleanliness functioned at the intersection of physical care, social norms, and religious expectations. To be clean meant more than removing visible dirt—it meant being in a state appropriate for interaction with others, with authority, and with the gods.

Water played a central role in this system. Cuneiform texts repeatedly refer to washing, bathing, and rinsing as essential acts, both in everyday routines and before formal rituals. In several contexts, water itself is described as inherently “clean,” capable of neutralizing contamination and restoring order.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Rather than focusing on health in the modern sense, Hittite hygiene emphasized control, suitability, and balance within a carefully regulated society.

Detergents Before Soap

One of the study’s most striking findings concerns the materials used for cleaning. The Hittites did not rely on water alone. Textual sources document the use of natron, ash, and plant-based substances comparable to soapwort—materials known to enhance the cleansing power of water.

These substances were applied to wash textiles, household objects, ritual equipment, and even people. Some ritual texts explicitly describe dirty linen becoming white after washing, language that suggests practical, visible results rather than purely symbolic actions.

Such descriptions point to a society familiar with effective cleaning processes, well before the appearance of manufactured soap.

Archaeological Evidence of Bathing Spaces

Archaeology supports the textual record. Excavations at major Hittite centers, including Hattusa, Sarissa, Oymaağaç, and Tarsus, have revealed ceramic bathtubs and purpose-built washing spaces.

These bathtubs were often large, carefully shaped, and installed in rooms with waterproof floors and drainage systems. Some feature handles or seating elements, indicating repeated and deliberate use. Nearby vessels, likely used for pouring water or storing oils, further reinforce the interpretation of these spaces as dedicated hygiene areas.

In several settlements, researchers suggest that bathtubs may have been present in most houses—a remarkable level of domestic infrastructure for the Late Bronze Age.

Hygiene and Social Hierarchy

Cleanliness was not practiced equally across all levels of society. Social status influenced access to materials and facilities. In royal and elite contexts, washbasins made of copper, bronze, and even silver are documented. These were heavy, functional objects designed for regular use rather than ceremonial display.

Texts describing palace life reveal an intense concern with contamination. In one account, a Hittite king reportedly reacted with anger after discovering a single hair in his wash water, ordering stricter filtering measures. Such details highlight how cleanliness was closely tied to royal authority, dignity, and control.

Washing Before the Gods

Religious life imposed the strictest hygiene requirements. Priests, temple workers, and individuals preparing offerings were expected to bathe, groom themselves, trim hair and nails, and wear freshly washed garments.

Before rituals, kings and queens followed carefully prescribed sequences of hand washing and drying. Physical uncleanliness could render a person unfit to approach the divine.

The study also draws a crucial distinction: being clean did not automatically mean being ritually pure. Cleanliness was a prerequisite, but certain actions or exposures required additional ritual procedures to restore full religious purity.

Rethinking Hittite Daily Life

Taken together, the evidence reveals a society with a highly developed understanding of hygiene—one that combined practical cleaning methods with symbolic meaning. The Hittites filtered water, used detergent-like substances, constructed bathing spaces, and enforced strict rules governing cleanliness.

Rather than viewing ancient hygiene as primitive or incidental, this research invites a reassessment. In the Hittite world, cleanliness shaped homes, rituals, and hierarchies, reflecting a disciplined approach to daily life that resonates strongly with modern expectations.

The findings offer a more intimate view of an ancient Anatolian civilisation—one defined not only by treaties, warfare, and gods, but also by baths, clean garments, and a carefully maintained sense of order.

Arroyo A. Hittite cultural conventions on hygiene. Anatolian Studies. 2025;75:29-45. doi:10.1017/S0066154625000055

Cover Image: This image was created using artificial intelligence as an interpretative illustration inspired by archaeological evidence and current scholarly research. It does not depict a specific historical event or excavation.

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply