Not Italian, but Anatolian: The Marble of Otto the Great’s Sarcophagus Traced to Marmara Island

For centuries, the monumental tomb of Otto I, known as Otto the Great, has stood at the heart of Magdeburg Cathedral as one of Europe’s most powerful symbols of medieval authority. Now, new scientific analyses have revealed that a crucial element of this imperial monument is not European at all, but Anatolian in origin.

Experts working on the ongoing conservation of Otto the Great’s sarcophagus have identified the marble cover of the tomb as Prokonnesian marble, quarried on Marmara Island in northwestern Türkiye. The finding not only revises long-standing assumptions about the material used in the emperor’s burial, but also highlights the deep and often overlooked role of Anatolia in shaping medieval European power symbols.

A tomb under scientific scrutiny

Since January 2025, the tomb of Otto the Great has been undergoing an extensive conservation program led by the Cultural Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt and the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology (LDA) Saxony-Anhalt. The project focuses on stabilizing the stone sarcophagus as well as studying the wooden coffin and skeletal remains housed within.

As part of this work, specialists removed the sarcophagus lid for detailed examination. While it was already known that the body of the sarcophagus was carved from limestone, the lid stood out for its white marble with dark grey banding, a material long assumed to have come from Italy or Greece.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Marble traced to Marmara Island

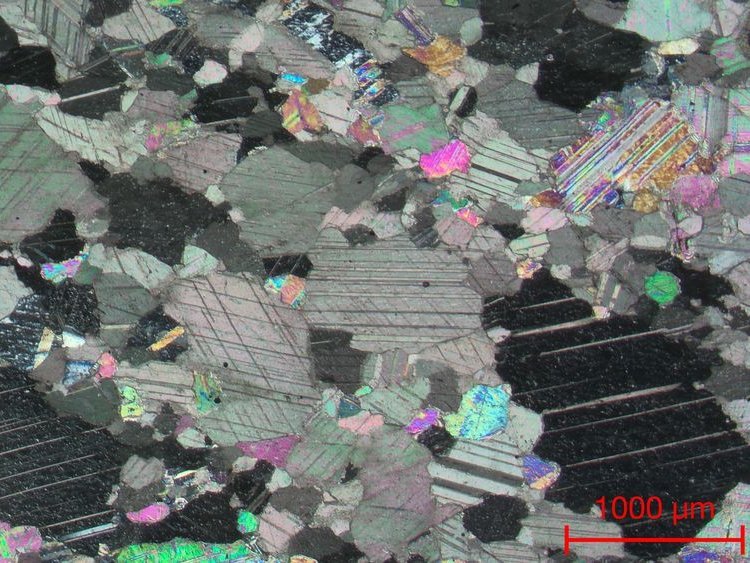

To determine the marble’s origin, stone experts from Vienna and Bochum conducted microscopic and geochemical analyses on small drill samples taken from both the light and dark zones of the slab. The results were compared with an extensive reference database of approximately 7,500 marble samples from ancient quarries across the Mediterranean, Northern Italy, and the Alpine regions.

The conclusion was unambiguous: the marble does not come from Carrara in Italy, nor from Cipollino quarries on the Greek island of Euboea. Instead, it originates from the ancient quarries of Prokonnesos, today’s Marmara Island, where marble extraction has been documented since at least the 7th century BCE.

Prokonnesian marble is distinguished by its predominantly white appearance and sharply defined grey bands, a visual signature that made it highly prized in antiquity and Late Antiquity.

A Late Antique stone with a long journey

The cutting pattern of the marble provided further clues. Unlike earlier Prokonnesian blocks, whose veining typically follows the length of the stone, the bands on Otto’s sarcophagus lid are tightly folded, irregular, and cut at oblique angles. This stylistic feature suggests the slab was quarried and shaped during Late Antiquity, when such aesthetics were in vogue.

Comparable marble elements of this type are well known from Ravenna, Venice’s San Marco, and Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, where Prokonnesian marble was used extensively for columns, wall panels, and flooring. Based on these parallels, researchers believe the slab originally belonged to a monumental building in Italy, most likely Ravenna, before being reused centuries later.

Spolia and imperial symbolism

The team argues that the marble slab was likely removed from an older structure and transported north as spolia—a common medieval practice involving the reuse of prestigious architectural elements from the Roman world. Such materials carried not only aesthetic value, but also powerful symbolic meaning.

Otto the Great spent nearly a decade in northern Italy, and the appropriation of antique or Late Antique building materials from Rome and Ravenna was a well-established way for rulers to visually associate themselves with imperial Roman authority. Directly importing raw marble from Marmara Island during Otto’s lifetime would have been logistically and politically implausible, strengthening the case for reuse.

Anatolia at the heart of European history

The discovery underscores the far-reaching influence of Anatolian quarrying traditions on the architectural and political landscapes of Europe. Prokonnesian marble was one of the most widely distributed stones of the ancient world, and its presence in the tomb of a Holy Roman Emperor reveals how deeply interconnected Anatolia and medieval Europe truly were.

Far from being a peripheral supplier, Anatolia emerges once again as a central contributor to imperial identity, even in contexts long assumed to be purely European. As conservation work continues in Magdeburg, the marble from Marmara Island now tells a story that stretches from the quarries of the Sea of Marmara to the heart of the Holy Roman Empire.

Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt

Cover Image Credit: Tomb of Otto I in Magdeburg Cathedral – Public Domain

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply