Was Göbeklitepe Really About Male Power? New Study Reframes Taş Tepeler Rituals

For decades, the towering stone pillars of southeastern Türkiye have been read through a familiar lens: power, dominance, fertility cults, and the early emergence of male authority. The monumental sites of the Taş Tepeler region—especially Göbeklitepe—have often been interpreted as visual declarations of masculinity carved in stone.

But what if that assumption says more about modern archaeology than about the Neolithic itself?

A recent academic study proposes a striking alternative. Rather than seeing phallic imagery as a symbol of male dominance or social hierarchy, the research argues that it may have functioned as an active ritual instrument—part of ecstatic practices designed to alter perception and consciousness.

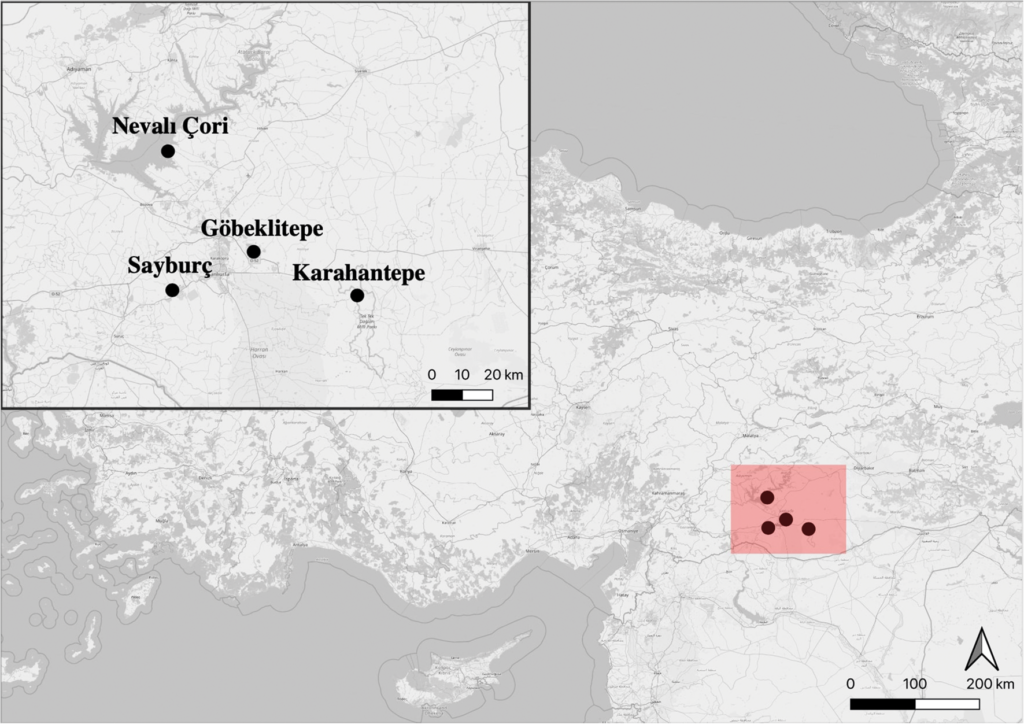

The study, titled A Queer Feminist Perspective on the Early Neolithic Urfa Region, was written by archaeologist Emre Deniz Yurttaş. Its focus spans multiple Taş Tepeler sites, including Sayburç, Karahantepe, Nevalı Çori, and Göbeklitepe.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The argument does not project modern identities into the past. Instead, it questions a long-standing interpretive habit: the automatic equation of the phallus with power.

Why Sayburç Forces a Rethink

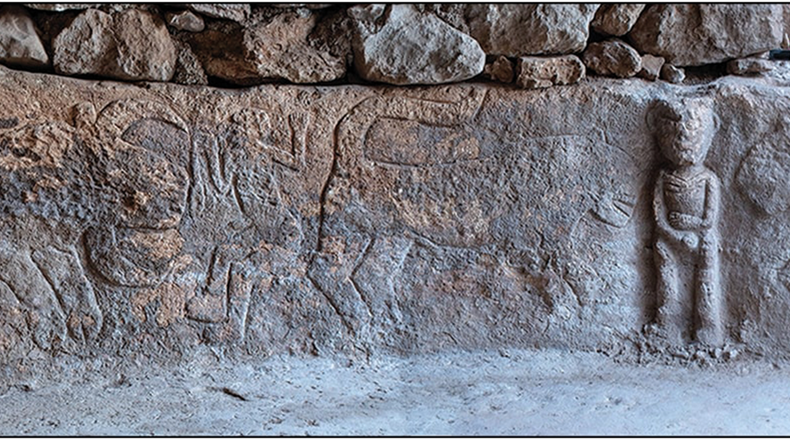

The most compelling evidence comes from Sayburç. One relief depicts a seated human figure grasping an erect phallus, flanked by animals. Unlike more abstract examples elsewhere, this scene is direct and unmistakably action-oriented.

Earlier interpretations often softened such imagery, framing erections as metaphors for authority or control over nature. The Sayburç relief resists that abstraction. The figure is not simply marked by a phallus—it is interacting with it.

Yurttaş shifts the central question. Instead of asking whose body is this? he asks: what is this body doing?

Across Taş Tepeler sites, phallic imagery consistently appears in an aroused state. Yet it rarely appears in reproductive or penetrative contexts. There is no clear pairing, no narrative of dominance. Instead, the images suggest repetitive, performative bodily acts.

That distinction matters.

Ecstasy, Not Hierarchy?

Anthropological research has long documented that many non-industrial societies use embodied techniques—dance, rhythm, intoxication, and sexual stimulation—to induce trance states. These are not marginal behaviors; they are ritual technologies.

Yurttaş situates Taş Tepeler within a similar animistic worldview. In such systems, humans, animals, and objects are not sharply divided. They exist in relational continuity.

The dynamic animal reliefs found across the region support this reading. Hybrid forms, exaggerated postures, and intense bodily imagery suggest that ritual life may have revolved around altered states of perception rather than structured authority.

If so, the phallus was not a symbol of dominance. It was a mechanism—an instrument capable of producing rhythm, sensation, and intensity.

Stones That Act

Another important dimension of the study concerns the role of stone itself. In many animistic traditions, objects are not passive representations. They are active participants in ritual life.

The carved pillars of Göbeklitepe and Karahantepe may not have merely depicted ecstatic states—they may have extended them. Ethnographic parallels show that objects can be perceived as storing or transmitting spiritual force. If this logic applied in the Neolithic, carved reliefs were not symbolic decorations but ritual technologies embedded in architecture.

This possibility destabilizes a long-standing narrative. If ecstatic agency could reside in stone, ritual authority was not confined to elite individuals.

An Egalitarian Neolithic?

Crucially, the archaeological record of Taş Tepeler does not support strong social stratification. There is little evidence for elite burials, wealth concentration, or rigid hierarchy. Communities appear to have been organized around shared ritual practices.

Within such a framework, reading phallic imagery as an emblem of male dominance becomes difficult to sustain.

Instead, Yurttaş suggests that ecstasy—rather than power—may have been the organizing principle of ritual life in Neolithic Anatolia.

Why This Debate Matters

This reinterpretation does not sensationalize the past. Nor does it impose modern categories. Rather, it exposes how modern assumptions—particularly the automatic linkage of sexuality with power—have shaped archaeological interpretation for decades.

The Taş Tepeler sites remind us that the Neolithic was not only a period of architectural innovation. It may also have been an era of experimentation—with bodies, perception, and transcendence.

Göbeklitepe is often described as the “world’s first temple.” But perhaps it was also something else: a space where bodies, animals, and stones converged in rituals that challenge contemporary expectations.

Archaeology is still learning how to speak about ecstasy. Taş Tepeler may be forcing that conversation.

Yurttaş E. D. “A Queer Feminist Perspective on the Early Neolithic Urfa Region: The Ecstatic Agency of the Phallus.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 2025;35(3):489-503. doi:10.1017/S0959774325000083

Cover Image Credit: The Sayburç Relief. (Özdoğan Reference Özdoğan 2022, fig. 4; photograph: Bekir Köşker.) Credit: Yurttaş E. D. (2025), Cambridge Archaeological Journal

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply