When a Village Courtyard Hid a King: The Neo-Hittite Reliefs of Sakçagözü

In southeastern Anatolia, near the modern village of Sakçagözü, an extraordinary chapter of Neo-Hittite art once lay in plain sight—embedded not in a museum wall, but in an ordinary village courtyard. What appeared to be a utilitarian stone block was, in fact, a monumental royal relief dating to the 8th century BC, carved for a palace complex at Coba Höyük.

A mound that drew attention early

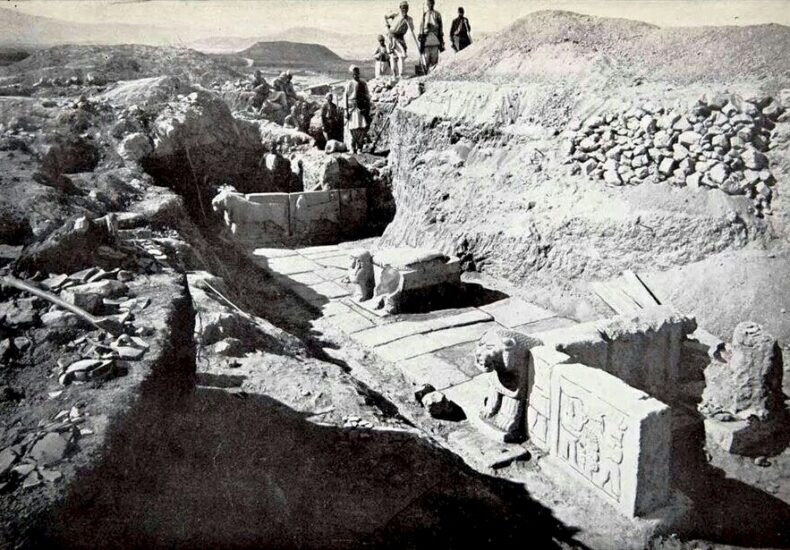

Coba Höyük attracted scholarly interest as early as 1883, when German researchers documented sculpted stones scattered across the mound and its surroundings. At the time, the site’s importance was only partially understood. Several carved blocks had been displaced, reused, or left exposed, their original architectural context lost.

More systematic excavations followed between 1908 and 1911, revealing the remains of a monumental Neo-Hittite palace. The complex featured decorated entrances lined with basalt orthostats, a characteristic element of Iron Age elite architecture in southeastern Anatolia and northern Syria. These reliefs were designed not merely to adorn walls, but to communicate authority to anyone approaching the palace.

A king revealed in stone

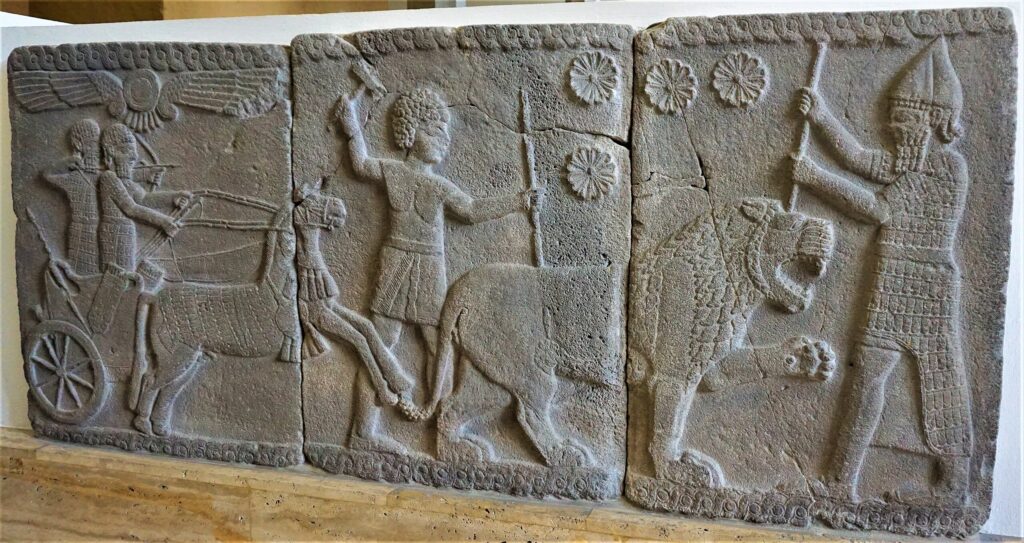

Among the most striking discoveries from Sakçagözü is a three-part basalt orthostat depicting a king engaged in a lion hunt. The scene is far from anecdotal. In Neo-Hittite visual language, the lion represents chaos and untamed power, while the king’s dominance over the animal asserts his role as protector of order.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Above the ruler appears a sun disk, a potent symbol of divine sanction and royal legitimacy. Its placement signals that kingship is not only political but cosmological, grounded in a sacred order inherited from Late Bronze Age Hittite traditions and consciously revived by Iron Age successor states.

The carving style reinforces this message. Strong outlines, frontal poses, and emphatic musculature create an image meant to impress, even intimidate. These reliefs were statements of power, positioned precisely where subjects and visitors could not ignore them.

From courtyard stone to museum masterpiece

Remarkably, this royal image spent part of its modern history as a functional stone in a village courtyard, stripped of its original meaning. Its significance became clear only through archaeological recognition in the late 19th century.

In 1883, the relief was acquired by Karl Humann, a central figure in early Anatolian archaeology. Transported to Germany, it eventually entered the collection of Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, where it remains one of the most important Neo-Hittite sculptures preserved outside Anatolia.

Sakçagözü in the Neo-Hittite landscape

The orthostats of Coba Höyük place Sakçagözü firmly within the cultural world of the Neo-Hittite principalities, which emerged after the collapse of the Hittite Empire. These polities preserved imperial artistic conventions while adapting them to new political realities, producing a hybrid visual language that bridged memory and innovation.

Today, the Sakçagözü reliefs are understood not simply as architectural decoration, but as visual declarations of kingship—messages carved in stone, once guarding palace gates, later overlooked in village life, and now recognized as masterpieces of Iron Age Anatolia.

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply