A 4,000-Year-Old Will from Kayseri’s Kültepe: “No Furniture Shall Leave the House.”

“No furniture shall leave the house.”

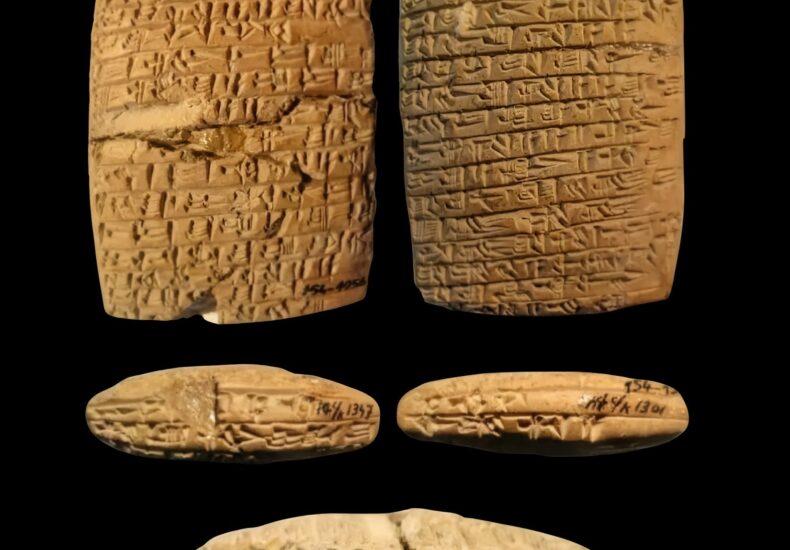

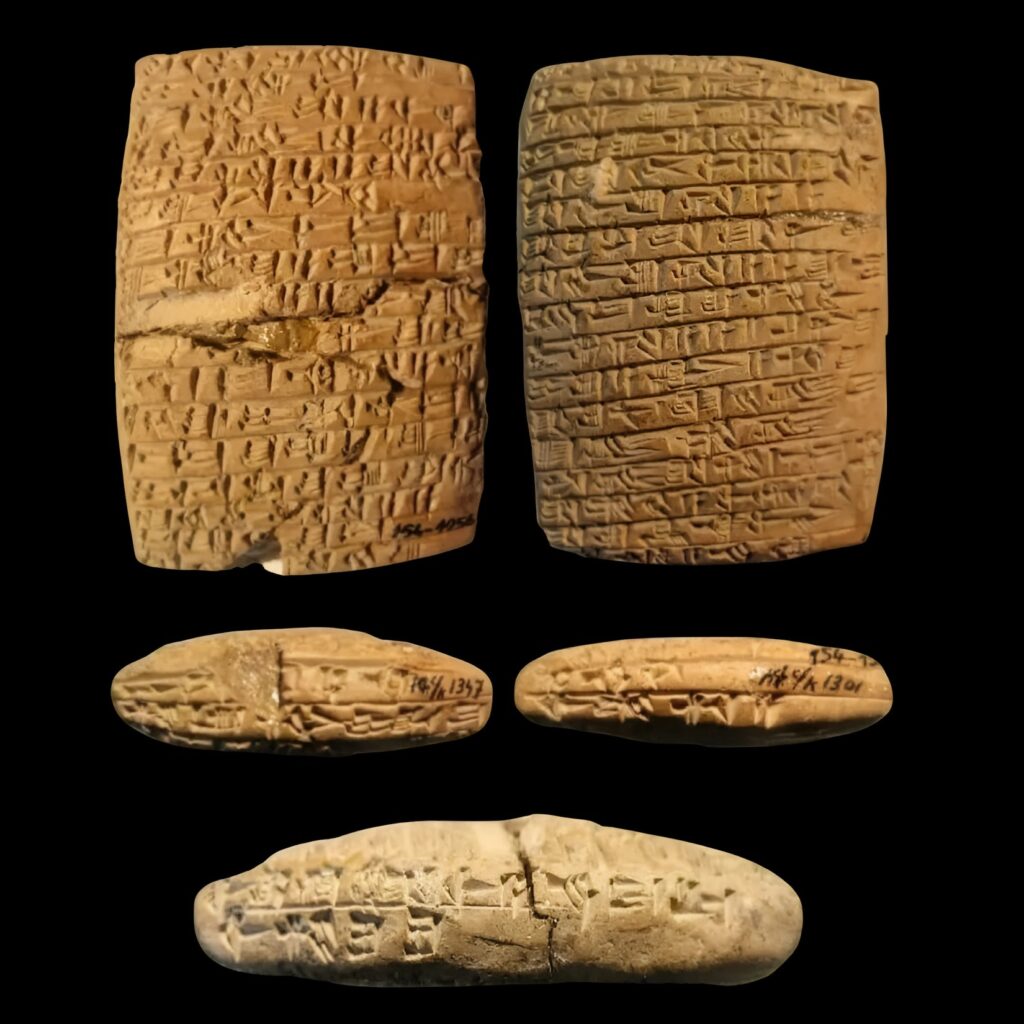

This phrase, inscribed in cuneiform on a clay tablet found at Kültepe (ancient Kaniš), might not sound unfamiliar to the modern legal ear. But its true weight becomes clear when one learns that it dates back to around 1900 BCE—making it one of the earliest known examples of a written will in human history.

The document in question is the last will and testament of the Assyrian merchant Šu Ištar, discovered during excavations at Kültepe in present-day Kayseri, Türkiye. More than a mere allocation of assets, this tablet represents one of the earliest documented instances of inheritance, property rights, and contractual obligations.

Šu Ištar: A Merchant in a Connected Ancient World

Šu Ištar was likely one of the many Assyrian merchants active in the city of Kaniš. These traders operated a vibrant long-distance trade network between Mesopotamia and Anatolia, exchanging silver and textiles for tin and other valuable goods. Business transactions were meticulously recorded on clay tablets using Old Assyrian cuneiform, and among these records, Šu Ištar’s will stands out as a rare glimpse into personal legal affairs.

The Tablet: Translation of the Will

Remarkably well-preserved (with only a few damaged lines), the tablet outlines how Šu Ištar’s estate is to be divided, detailing silver distributions, property rights, the legal status of women, and even interest-bearing transactions.

“Šu Ištar has determined the fate of his house (he made a will):

The house in Aššur, the female slaves, the male slaves belong to Buzutáya of Kutáya. No furniture is to be removed from the house; they are hers as well.

When Buzutáya settles my accounts with my investors, she shall give 1 mina of silver to each of my brothers. They shall not raise any claim against her.

Šat-ilí shall live with Buzutáya. If they do not continue to live together, Buzutáya shall loan 3 talents of copper at interest, and Šat-ilí shall consume the interest. She shall not touch the principal copper.

Šat-ilí shall reside in the back of the house. Her estate belongs to Buzutáya.

Buzutáya shall receive 2 shares of the silver left by Šu Ištar. His brothers shall each receive one share.

The house in Zimizhuna, along with the female and male slaves, is my concubine’s. Her estate belongs to Su’en-nawir, Ennam-Aššur, and Aššur-táb.

Witnesses: Amríya, Elálí, Aššur-malik, Šilulu.”

What the Will Reveals: Society and Law in Ancient Anatolia

Though this may appear to be a private matter of inheritance, it offers profound insights into the legal, social, and economic structures of the period.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

1. Women’s Right to Own Property

Notably, Buzutáya and Šat-ilí—both women—are designated as legal heirs. They inherit houses, slaves, silver, and even the right to loan capital at interest. The will also assigns property to a concubine, suggesting that even non-married women could hold and transmit property. This implies a surprisingly inclusive and nuanced legal framework.

2. Advanced Financial Instruments

The clause stating that copper shall be lent out and the interest consumed, while the principal remains untouched, reflects a basic understanding of investment and financial returns. This predates many commonly known interest-bearing financial systems by millennia.

3. Legal Formality and Witnesses

The presence of four named witnesses underscores the importance of legality and public affirmation. This wasn’t merely a written document—it was a binding legal act, validated by community members, showing that law and record-keeping were central to ancient Assyrian and Anatolian culture.

A Legacy in Clay: The Enduring Power of Writing and Law

The will of Šu Ištar is not just one man’s final wish. It is a 4,000-year-old legal document that embodies the essence of civilization: the ability to record, transmit, and enforce rights beyond one’s lifetime. It also reminds us that the core principles of modern law—witnesses, inheritance, financial contracts, and gendered property rights—were already present in ancient Anatolia.

Today, this humble clay tablet stands among the earliest testaments to the power of law and literacy. Through it, we glimpse a world where trade, family, and law intersected—and where the written word gave shape to memory, identity, and justice.

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply