Byzantium’s Forgotten Defense Line: The 1,500-Year-Old Anastasian Wall

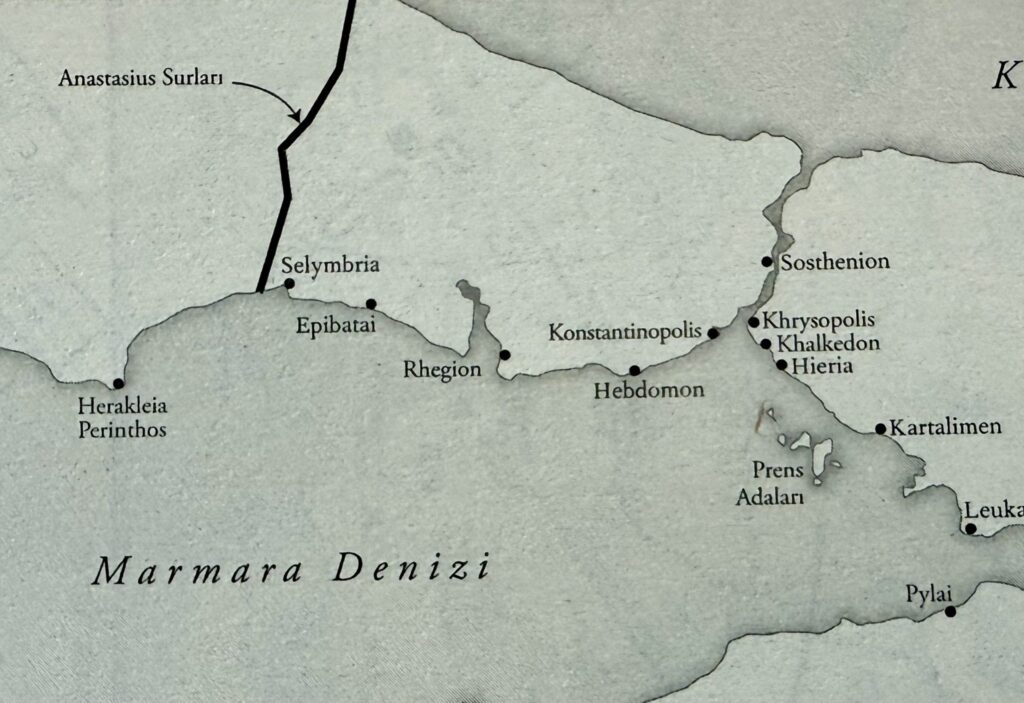

Few visitors exploring Istanbul’s historic treasures know that 65 kilometers west of the city, hidden among forests and fields, lies one of Byzantium’s most ambitious but forgotten fortifications: the Anastasian Wall, also known as the Long Walls of Thrace. Built in the early 6th century under Emperor Anastasios I, this massive line of defense once stretched 46 kilometers from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara, forming a sea-to-sea barrier across the Thracian peninsula.

Why Was It Built?

After the crushing Roman defeat at the Battle of Adrianople in 378 CE, where Emperor Valens fell to the Goths, the empire recognized the urgent need for stronger defenses. While Constantinople’s Theodosian Walls secured the capital, its suburbs and farmlands remained exposed. To shield the region from Bulgar and other northern incursions, Anastasios commissioned this colossal fortification—described by contemporary sources as a feat that “surpassed even the walls of Themistocles in Athens.”

Towers, Moats, and Fortified Outposts

The wall itself was an engineering marvel of its age. Built with limestone and sandstone blocks bound by strong mortar, it reached up to 10 meters high and averaged 3 meters thick. In front of it stretched a 15-meter-wide moat, in some places reinforced to extraordinary lengths—such as the 80-meter ditch at the fortress known as Büyük Bedesten.

Every 80 to 120 meters, towers rose along the line—hundreds in total. Some were rectangular watchtowers, while others took on pentagonal or hexagonal forms, among the largest bastions of antiquity, designed to hold heavy artillery like torsion catapults. Between them stood smaller fortresses, called “bedestens”, built roughly every 3.5 kilometers to guard key passages.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The Landscape and Legacy

Archaeological surveys over the past 15 years have mapped much of the line: overgrown remains hidden in dense oak and beech forests, fragments scattered across fields, and even the submerged outline of a breakwater at the Marmara shore, a rare attempt to shield the fortifications from seaborne attack. The wall also protected vital resources such as the Pınarca water supply, underscoring its strategic role in sustaining Constantinople.

One inscription reused in a small church at Evcik records Emperor Herakleios (610–641) and his general Smaragdos, confirming repairs after 610 CE. Yet by the time of the Avar siege of 626, the line had already lost its function and was effectively abandoned.

More Than Stone

For the people of Constantinople, the Long Walls symbolized more than defense—they represented prestige. The chronicler Malalas even called it the “Wall of Constantinople,” a telling sign of its importance. In 558, the aging Emperor Justinian I personally oversaw repairs, proof that the wall stood not just as a military barrier but as a reflection of imperial authority and honor.

You may also like

- A 1700-year-old statue of Pan unearthed during the excavations at Polyeuktos in İstanbul

- The granary was found in the ancient city of Sebaste, founded by the first Roman emperor Augustus

- Donalar Kale Kapı Rock Tomb or Donalar Rock Tomb

- Theater emerges as works continue in ancient city of Perinthos

- Urartian King Argishti’s bronze shield revealed the name of an unknown country

- The religious center of Lycia, the ancient city of Letoon

- Who were the Luwians?

- A new study brings a fresh perspective on the Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages

- Perhaps the oldest thermal treatment center in the world, which has been in continuous use for 2000 years -Basilica Therma Roman Bath or King’s Daughter-

- The largest synagogue of the ancient world, located in the ancient city of Sardis, is being restored

Leave a Reply